Key characteristics

Trees and shrubs, with branches usually forked, and ending abruptly by a conspicuous leaf-bud. The leaves are opposite, simple, sometimes pinnated, as in the Ash. The flowers grow in racemes or panicles; the flower-stalks placed opposite each other with a single bract at the base. The flowers are either perfect, or have stamens and pistils on different flowers. The calyx is divided, persistent, below the ovary; the corolla is of one petal, four cleft at the top, occasionally of four petals connected in pairs by the intervention of the filaments of the stamens; sometimes the corolla is wanting. The stamens are generally two, in Tessandra they are four, alternate, with the divisions of the corolla, or with the petals; the anthers are two-celled, opening longitudinally. The ovary is simple, without any disk, two-celled, the cells two-seeded: the style is simple, or wanting; the stigma bifid or undivided. The fruit is eithe a drupe as in Olea; a berry as in Ligustrum; a capsule as in Syringa; or a winged samara, as in Fraxinus; often with only one perfect cell; the seeds have fleshy abundant albumen.

This tribe has, in many respects, affinity with the Jasmine tribe.

The chief character is the oil contained in the fleshy portion of the fruit instead of in the seeds.

Select plants in this order

Not all plants listed are illustrated and not all plants illustrated are listed.

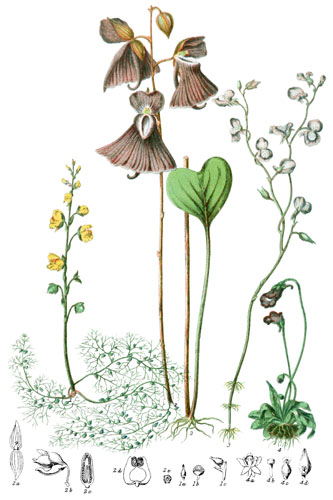

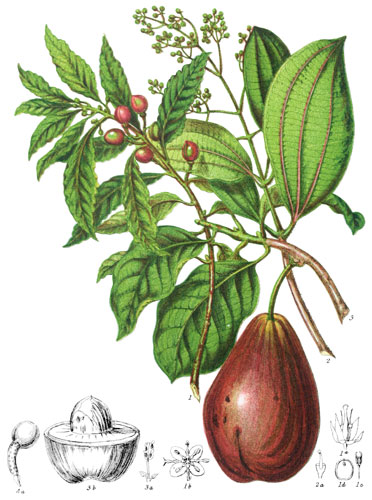

- Olea europæa (1), the most valuable plant of this tribe, has been highly esteemed in all ages and countries; in the earliest times, “the land of oil-olive” was an expression of the most desirable abundance; to flourish like a green olive-tree was descriptive of the greatest vigour and prosperity; it has also been considered as a token and emblem of peace since the memorable day when the dove came back to the Ark—“and lo! in her mouth was an olive-leaf.” The use of oil was early known to the inhabitants of the earth, and its value was so great that it became a symbol of the highest gifts and qualities. The olive-tree attains a great age; some at Terni are said to have existed in the time of Pliny. Although Asia is its native country, it is now perfectly naturalized in different parts of the south of Europe, thriving best on calcareous steems near the coast of the Mediterranean; on the Apennines, between Genoa and Spezia, the effect of the grey foliage, mingled with the bright green of the chesnut and the dark glossy leaves of the fig, is extremely picturesque. The unripe fruit, when prepared in salt and water, is thought an agreeable condiment by Italians and Spaniards; oil is obtained by pressure from the ripe fruit; the bark is bitter and astringent.

- O. fragrans is a low shrub with yellow flowers, which are odoriferous as well as the leaves, and much valued in China.

- O. excelsa is the largest tree that grows at 5000 feet on the Peak of Teneriffe.

- Syringa, the Lilac (2), now acclimatized in England, is become one of the most common and generally admired of shrubs, producing highly fragrant flowers in great abundance in May. In the time of Henry VIII., six licacs were mentioned in the gardens of Nonsuch as “trees which bear no fruit, but only a pleasant smell.” In the marshy districts of Berri, in France, the peasants employ the flowers as a remedy against the intermittent fever which prevails there.

- Ligustrum vulgare (3) grows wild in the Isle of Wight and other parts of England, and is one of those few hardy shrubs which can endure the smoky atmosphere of cities, although its delicate flowers come forth only in a purer air. An ever-green variety forms remarkably good hedges. When of sufficient size, the wood is useful; the berries yield a green dye for wool.

- L. lucidum produces a kind of vegetable wax in China.

- Fraxinus excelsior, the common Ash, is one of the most graceful as well as useful British trees: in form and foliage easily distinguished among other forest trees. In the Isle of Wight it grows remarkably well, and is particularly beautiful when the leaves acquire their peculiar pale golden hues in autumn.

- F. pendula (4) was first discovered in Gamblingay, in Cambridgeshire.

- F. rotundifolia and other species yield from the bark the Manna known and used medicinally, the sweetness of which is a distinct principle called Mannite, differing considerably from Sugar. Various species belong to North America; the yellow Ash grows about the branches of the Mississippi, where the large stems are burnt out into canoes by the French fur-traders, and serve to convey their stores to New Orleans. The outer bark is eight inches thick; the inner bark of a yellow colour.

Locations

The plants of this Tribe are chiefly natives of Temperate climates, approaching towards the Tropics, but scarcely found beyond 65° of north latitude. Fraxinus abounds in North America and Europe; Phyllirea and Syringa belong to Asia and Europe; one species is a native of Nepal; a few species have been discovered in Australia.

Legend

- Olea Europæa, Olive-tree. South Europe.

- Calyx and Pistil.

- Flower.

- Stone of Fruit.

- Syringa vulgaris, Common Lilac. Persia.

- Calyx and Pistil.

- Flower, opened.

- Capsule.

- Ligustrum vulgare, Common Privet. Britain.

- Flower, magnified.

- Section of Fruit.

- Fraxinus pendula, Drooping Ash. England.

- Flower, magnified.

- Seed.

Explore more

Posters

Decorate your walls with colorful detailed posters based on Elizabeth Twining’s beautiful two-volume set from 1868.

Puzzles

Challenge yourself or someone else to assemble a puzzle of all 160 botanical illustrations.