Enlarge

Enlarge

British Mineralogy

Pit-Coal

- Class 1. Combustibles.

- Order 2. Mixed.

- Gen. 6. Carbon.

- Spec. 1. Bituminous.

- Spec. Char. Bituminous oxide of carbon, and oxide of carbon; mixed.

- Syn.

- Mineral Carbon impregnated with bitumen. Kirw. 2. 51.

- Bitumen Lithanthrax*. Linn. Syst. Nat. ed. 13. t. 3. p. 111.

- Steinkhole. Emmerl. 1. 60.

- Houille. Haüy 3. 316. De Lisle 2. 590.

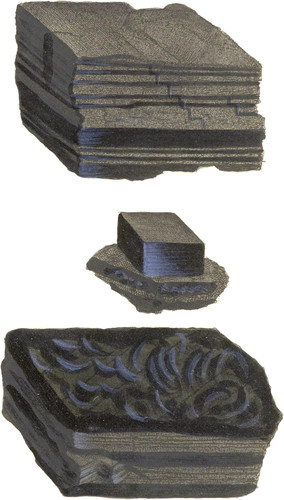

Coal is a curious, valuable, and well-known article in Great Britain, supplying us with great store of excellent fuel. There are many varieties in different mines, and even in the same mine. The upper figure is taken from a common Newcastle specimen, from whence a great part of England, and many parts of the Continent, are supplied. It is evidently composed of two sorts of strata, to external appearance sufficiently distinct. The one apparently the remains of wood in a charred state, like charcoal or oxide of carbon. This has hitherto escaped the notice of most authors: besides the grain and appearance of wood, common in this and most other coals, it will be known by being the only part in coal that soils the fingers. If separated, it burns like charred wood, leaving a similar residuum†; it is also soft and powdery, like burnt wood; breaks in a crumbling manner, and falls into small particles‡. The other part is more compact, shining, and brittle, easily scratched with a knife. The least touch of the finger hurts its polish. It has somewhat splintery conchoidal fracture, and seems chiefly carbon mixed with bitumen. It inflames in a moderate heat, yields much smoke, bubbles, and melts something like pitch, and helps the binding or caking, as it is called, (which is the sign of a good coal, at least for housekeeping) and leaves a cinder which lasts a great while, giving a strong heat. The small remains from a common fire are still valuable on that account for the forge. If burnt long in a violent draught of air, it forms a clinker of no value; which shows it to contain some silex, and, perhaps, iron. Coals are not known to crystallize, yet this glosy part in many has a regular disposition towards it in the partings; and these mostly have the same angles, forming an upright prism with rhomboidal bases, the angles of which are about 84° and 96°§.

The middle figure in this plate is a fragment of the Newcastle coal; the completest crystal-like apparance I ever saw. The upper surface is charcoaly, and it rests on a similar substance, with irregular strata beneath.

Newcastle coal loses about 35 per cent. of its weight while flaming.

Linnæus’s description seems to belong to the more slaty kind.

The lower figure is from a piece of Scotch coal, which was broke through the bituminous strata, in a transverse direction: an dshows the glossy fracture, with a sattiny appearance, as well as the angles of partings. This bituminous stratum is commonly somewhat shaly in this sort of coal: the other part is mostly pure charcoal, and often exhibits the shape of branches compressed, and the same transverse contractions which take place in charring or burning common deal. This coal loses 25 per cent. while flaming, which it readily does, and continues its heat with very little bubbling; flaking and falling to pieces in a slaty form, leaving a whitish ash.

Mr. Kirwan describes Scotch coal from Irwine as “having layers in contrary directions, and being hence often called Ribband Coal. Lustre of the alternate layers 3, 2, (silky and brighter.) Fracture small grained, and coarse grained, curved, foliated. Hardness 4 to 5. Spec. Grav. 1.259. Its composition I have not examined.”

Mr. Kirwan’s description is very good, but, for the most part, will agree with any stratified coal, viz. the Newcastle, Chesterfield, Staffordshire, &c. But this we need not wonder at, from his not having examined the component parts.

I have a coal from Boroughstoness, given me by Dr. P. Murray, of the kind above described, and some said to be passing into splint, varieties of which are found at Newcastle, Wiggan, and other places. These are often confounded with the Box Coal or Cannel Coal of Kirwan, v. 2. p. 52, the true sort, which is now very scarce. Of these we shall give a fuller account hereafter.

We were favoured by Mr. E. D. Clarke of Jesus College, Cambridge, in February 1804, with specimens of Lynn Coal, presenting pentaëdral prisms, which he has observed in it for more than a year past. Other coals present this figure, and also trihedral prisms. These are produced by a fracture parallel to one of the diagonals of the base of the tetraëdral prism.

- * Linnæus included all coals under this title, describing them as schistose, which does not include all the species.

- † We have reason to believe that it contains no alkali.

- ‡ Mr. Jameson says, “this does not seem a common appearance,” when he found “carbonized wood which could not be distinguished from cabonized Fir.” v. 2. p. 87. It is probably the smut of Mr. Kirwan.

- § Most mixed coals in the common large masses break through the whole stratum more or less in this form: these breaks or cracks are called backs, cutters, and partings, by the miners.