Proof reading

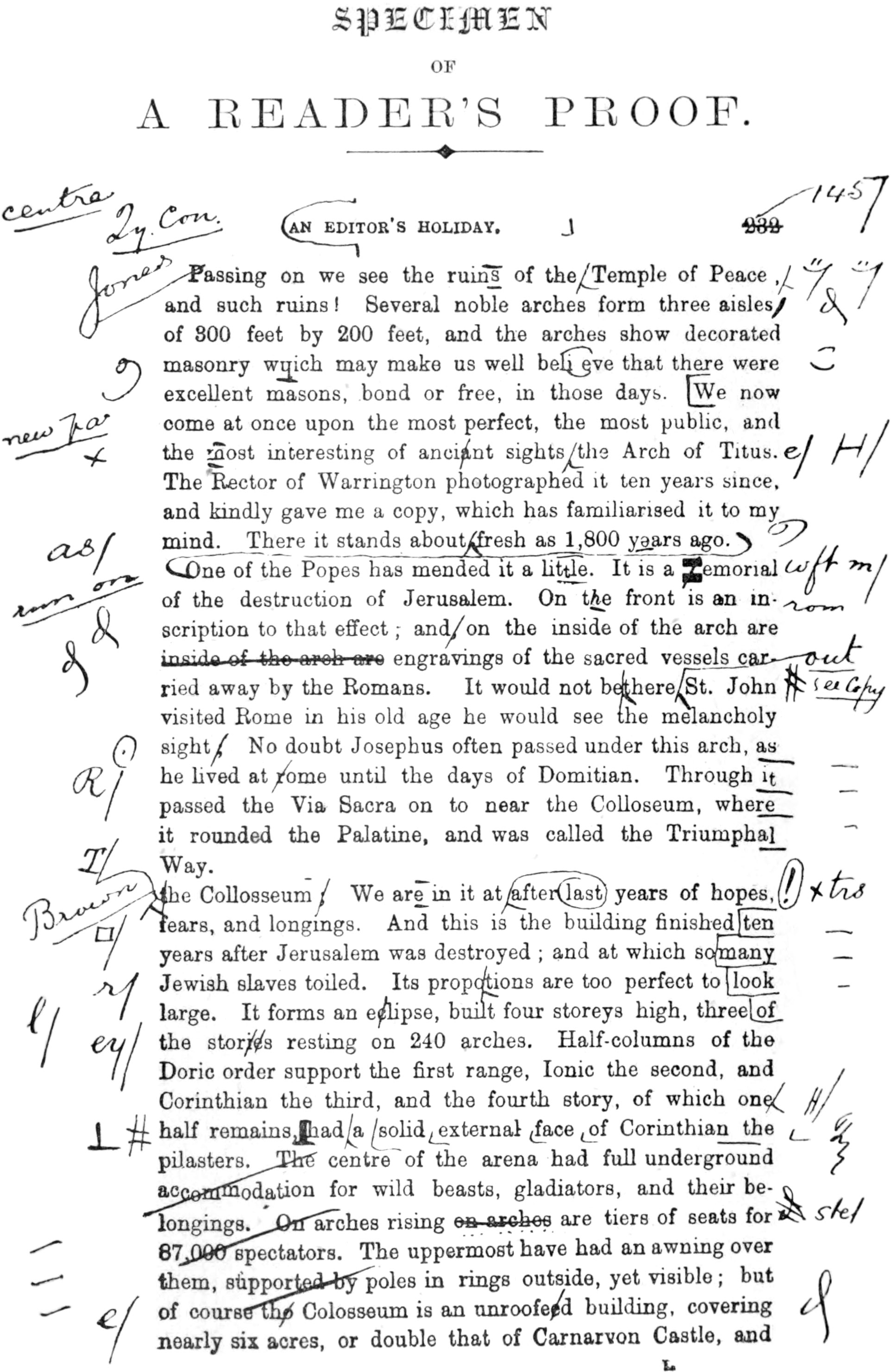

The art of correcting proofs (See Reader). The following description of the modus operandi is adapted from the “Encyclopædia Britannica:”—

The Reader, having folded the proof in the necessary manner, first looks over the signatures, next ascertains whether the sheet commences with the right signature and folio, and then sees that the folios follow in order. He now looks over the running heads, inspects the proof to see that it has been imposed in the proper furniture, that the chapters are numbered rightly, and that the directions given have been correctly attended to, marking whatever he finds wrong. Having carefully done this, he places the proof before him, with the copy at his left hand, and proceeds to read the proof over with the greatest care, referring occasionally to the copy when necessary, correcting the capitals or Italics, or any other peculiarities, noting continually whether every portion of the composition has been executed in a workmanlike manner.

Having fully satisfied himself upon these and all technical points, he calls his reading boy, who, taking the copy, reads in a clear voice, but with great rapidity, and often without the least attention to sound, sense, pauses, or cadence, the precise words of the most crabbed or intricate copy, inserting without pause or embarrassment every interlineation, note, or side-note. The gabble of these boys in the reading room, where there are three or four reading, is most amusing, a stranger hearing the utmost confusion of tongues, unconnected sentences, and most monotonous tones.

The Readers, plodding at their several tasks with the most iron composure, are not in the least disturbed by the Babel around them, but follow carefully every word, marking every error, or pausing to assist in deciphering every unknown or foreign word. This first reading is strictly confined to making the proof an exact copy of the manuscript, and ascertaining the accuracy of the composition; consequently, first readers are generally intelligent and well educated compositors, whose practical knowledge enables them to detect the most trivial technical errors. Having thus a second time perused the proof, and carefully marked upon the copy the commencement, signature, and folio of the succeeding sheet, he sends it by his reading boy to the composing-room, to be corrected by the workmen who have taken share in the composition. These immediately divide the proof amongst them, and each corrects that portion of it which contains tin- matter he has composed.

When every compositor has corrected his matter, that one whose matter is last on the sheet locks it up, and another proof is pulled, which, with the original proof, is taken to the same first reader, who compares the one with the other, and ascertains that his marks have been carefully attended to, in default of which he again sends it up to be corrected; but should he find his revision satisfactory, he sends the second proof with the copy to the second Reader, by whom it undergoes the same careful inspection: but this time, most technical inaccuracies having been rectified, the reader observes whether the author’s language be good and intelligible; if not, he makes such queries on the margin as his experience may suggest; he sends it up to the compositor, when it again undergoes correction, and, a proof being very carefully pulled, it is sent down to the same reader, who revises his marks and transfers the queries.

The proof is then sent, generally with the copy, to the author for his perusal, who, having made such alterations as he thinks necessary, sends it back to the printing-office for correction. With the proper attention to these marks, the printer’s responsibility as to correctness ceases, and the sheet is now ready for press.

Such, at least, is the process of proof reading which ought to be adopted; but now, from the speed with which works are hurried through the press, the proofs are frequently sent out with but one reading, the careful press reading being reserved until the author’s revise is returned. “Hansard’ Typographia” (1825), p. 748, gives some useful remarks on this subject.

It is always desirable that a Reader should have been previously brought up to the business as a compositor. By his practical acquaintance with the mechanical departments of the business he will be better able to detect those manifold errata, which, when suffered to pass, give an air of carelessness and inattention to his labours, that must always offend the just taste and professional discernment of all true lovers of correct and beautiful typography. Some of the principal imperfections which are most easily observed by the man of practical knowledge in the art of printing are the following, viz.: imperfect and wrong founted letters; inverted letters, particularly the lower-case s, the n u, and the u n; awkward and irregular spacing: uneven pages or columns; a false disposition of the reference mark; crookedness in words and lines; bad making-up of matter: erroneous indenting, &c. These minutiæ, which are rather imperfections of workmanship than literal errors, are apt to be overlooked and neglected by those Readers who have no idea of the great liability there is, even with the most careful compositor, to fall into them—nay, the almost absolute impossibility of wholly avoiding them.

A Reader ought not to be of a captious or pedantic turn of mind, the one will render his situation and employment extremely unpleasant, and the other will tempt him to habit, destructive of that consistency of character in his profession which he ought ever scrupulously to maintain. We are here alluding to a strict uniformity in the use of capitals, in orthography, and punctuation. Nothing, indeed, can he more provoking to an author than to see—for instance—the words honour, favour, &c., spell with the u in one page, and, perhaps, in the next modernised, and spelt without that vowel. This is a discrepancy which correctors of the press should always carefully avoid. The like observations will apply to the using of capital letters to noun substantives. &c., in one place, and the omission of them in another. Whatever may be the different opinions or practices of authors in these respects, the system of spelling. &c. must not he changed in the same work.

The reading-boy should be able to read with ease and distinctness any copy put into his hands, and he should be instructed not to read too fast, but to pay as much attention to what he is engaged on as if ho were rending for his own amusement or instruction. The eye of the Header should not follow, but rather go before, the voice of the reading-boy; for, by a habit of this nature, a Reader will, as it were, anticipate every single word in his copy; and when any word or sentence happens to have been omitted in the proof, his attention will the more sensibly be arrested by it. when he hears it pronounced by his reading-boy. Great care, however, ought to be paid, least the eye of the Reader should go too far before the words of his reading-boy. For as he will be apt to be attending to the meaning of his author, he will read words in the proof which actually do not appear there, and the very accuracy of the reading-boy will but tend to confirm him in the mistake.

In revising a proof-sheet, particular care must be taken that none of the fresh errors escape, which compositors often make in the course of correcting the original ones. To avoid this, the Reader ought not only to pay attention to the particular word which been corrected, but always to read over with care the whole of the line in which that word is to be found. This is particularly necessary in cases where it has been requisite for the compositor to alter irregular or slovenly spacing; for in raising the line in the metal for that purpose, there is very great danger of some word or letter falling out, or some space being put into a wrong place.

In offices where more Readers than one are employed it is always advisable that a proof-sheet should be read over by at least two of the Readers. The eye in going over the same track is liable to be led into the same mistake or oversight. The interest excited by the first or second reading having abated, a degree of listlessness also will steal upon the mind, extremely detrimental to correctness in the proof. It ought always to be remembered that the part of the copy which contains the connecting matter of the ensuing sheet must either be retained, or carefully transcribed, or read off, a proof of that matter having been pulled for that purpose.

Authors are very apt to make alterations, and to correct and amend the style or arguments of their works when they first see them in print. This is certainly the worst time for this labour, as it is necessarily attended with an expense which, in large works, will imperceptibly swell to a large sum; when, however, this method of alteration is adopted by an author, the Reader must always be careful to read the whole sheet over once more with very great attention before it is finally put to press.

A proof-sheet having duly undergone this routine of purgation, may be supposed as free from errata as the nature of the thing will admit, and the word “Press” may be written at the top of the first page of it. This is an important word to every Reader if he have suffered his attention to be drawn aside from the nature of his proper business, and errors should be discovered when it is too late to have them corrected. This word “Press” is as the signature of the death-warrant of his reputation; and if he is desirous of attaining excellence in his profession will occasion an uneasiness of mind which will but ill qualify him for reading other proof-sheets with more care and correctness.

A Reader should, therefore, be a man of one business, always upon the alert, all eye, all attention. Possessing a becoming reliance upon his own powers, he should never be too confident of success. Imperfection clings to him on every side, errors and mistakes assail him from every quarter. His business is of a nature that may render him obnoxious to blame, but can hardly be said to bring him in any very large stock of praise. If errors escape him he is justly to be censured, for perfection is his duty. If his labours are wholly free from mistake, which is, alas, a very rare case, he has done no more than he ought, and consequently can merit only a comparative degree of commendation, in that he has had the good fortune to be more successful in his labours after perfection than some of his brethren in the same employment.

No Reader should suffer his proofs to go to press, where there have been any material errata, without their receiving a last revision by himself. If he is doubtful of himself and diffident of his own powers of attention, how much more ought he to be on his guard respecting the care and attention of others! He should make it a rule never to trust a compositor in any matter of the slightest importance—they are the most erring set of men in the universe.

In the final operation of revising a form for press, the eye must be cast along the sides and heads of the respective pages least any letter should happen to have fallen out, any crookedness have been occasioned in the locking-up of the forme, or any battered letters have been inserted. These are the qualifications of a Reader; this the business of one employed as a Corrector of the Press. It is an arduous employment, an employment of no small responsibility, and which ought never to be entrusted to the intemperate, the thoughtless, the illiterate or the inex-perienced. “Chambers’s Encyclopædia,” Vol. III., p. 255, has an article on Correction of the Press.

In printing regular volumes, one sheet is usually corrected at a time but where extensive alterations, omissions, or additions are likely to be made by writer or editor, it is more convenient to take the proofs on long slips, before division into pages.

The thankless and monotonous business of a Corrector or Reader is more difficult than the uninitiated would believe. It requires extensive and varied knowledge, an accurate acquaintance with the art of typography, and, above all, a peculiar sharpness of eye, which, without losing the sense and correction of the whole, takes in at the same time each separate word and letter.

Proof reading

The art of correcting proofs (See Reader). The following description of the modus operandi is adapted from the “Encyclopædia Britannica:”—

The Reader, having folded the first proof in the necessary manner, first looks over the signatures, next ascertains whether the sheet commences with the right signature and folio, and then sees that the folios follow in order. He now looks over the running heads, inspects the proof to see that it has been imposed in the proper furniture, that the chapters are numbered rightly, and that the directions given have been correctly attended to, marking whatever he finds wrong. Having carefully done this, he places the proof before him, with the copy at his left hand, and proceeds to read the proof over with the greatest care, referring occasionally to the copy when necessary, correcting the capitals or Italics, or any other peculiarities, noting continually whether every portion of the composition has been executed in a workmanlike manner.

Having fully satisfied himself upon these and all technical points, he calls his reading boy, who, taking the copy, reads in a clear voice, but with great rapidity, and often without the least attention to sound, sense, pauses, or cadence, the precise words of the most crabbed or intricate copy, inserting without pause or embarrassment every interlineation, note, or side-note. The gabble of these boys in the reading room, where there are three or four reading, is most amusing, a stranger hearing the utmost confusion of tongues, unconnected sentences, and most monotonous tones.

The Readers, plodding at their several tasks with the most iron composure, are not in the least disturbed by the Babel around them, but follow carefully every word, marking every error, or pausing to assist in deciphering every unknown or foreign word. This first reading is strictly confined to making the proof an exact copy of the manuscript, and ascertaining the accuracy of the composition; consequently, first readers are generally intelligent and well educated compositors, whose practical knowledge enables them to detect the most trivial technical errors. Having thus a second time perused the proof, and carefully marked upon the copy the commencement, signature, and folio of the succeeding sheet, he sends it by his reading boy to the composing-room, to be corrected by the workmen who have taken share in the composition. These immediately divide the proof amongst them, and each corrects that portion of it which contains tin- matter he has composed.

When every compositor has corrected his matter, that one whose matter is last on the sheet locks it up, and another proof is pulled, which, with the original proof, is taken to the same first reader, who compares the one with the other, and ascertains that his marks have been carefully attended to, in default of which he again sends it up to be corrected; but should he find his revision satisfactory, he sends the second proof with the copy to the second Reader, by whom it undergoes the same careful inspection: but this time, most technical inaccuracies having been rectified, the reader observes whether the author’s language be good and intelligible; if not, he makes such queries on the margin as his experience may suggest; he sends it up to the compositor, when it again undergoes correction, and, a proof being very carefully pulled, it is sent down to the same reader, who revises his marks and transfers the queries.

The proof is then sent, generally with the copy, to the author for his perusal, who, having made such alterations as he thinks necessary, sends it back to the printing-office for correction. With the proper attention to these marks, the printer’s responsibility as to correctness ceases, and the sheet is now ready for press.

Such, at least, is the process of proof reading which ought to be adopted; but now, from the speed with which works are hurried through the press, the proofs are frequently sent out with but one reading, the careful press reading being reserved until the author’s revise is returned. “Hansard’ Typographia” (1825), p. 748, gives some useful remarks on this subject.

It is always desirable that a Reader should have been previously brought up to the business as a compositor. By his practical acquaintance with the mechanical departments of the business he will be better able to detect those manifold errata, which, when suffered to pass, give an air of carelessness and inattention to his labours, that must always offend the just taste and professional discernment of all true lovers of correct and beautiful typography. Some of the principal imperfections which are most easily observed by the man of practical knowledge in the art of printing are the following, viz.: imperfect and wrong founted letters; inverted letters, particularly the lower-case s, the n u, and the u n; awkward and irregular spacing: uneven pages or columns; a false disposition of the reference mark; crookedness in words and lines; bad making-up of matter: erroneous indenting, &c. These minutiæ, which are rather imperfections of workmanship than literal errors, are apt to be overlooked and neglected by those Readers who have no idea of the great liability there is, even with the most careful compositor, to fall into them—nay, the almost absolute impossibility of wholly avoiding them.

A Reader ought not to be of a captious or pedantic turn of mind, the one will render his situation and employment extremely unpleasant, and the other will tempt him to habit, destructive of that consistency of character in his profession which he ought ever scrupulously to maintain. We are here alluding to a strict uniformity in the use of capitals, in orthography, and punctuation. Nothing, indeed, can he more provoking to an author than to see—for instance—the words honour, favour, &c., spell with the u in one page, and, perhaps, in the next modernised, and spelt without that vowel. This is a discrepancy which correctors of the press should always carefully avoid. The like observations will apply to the using of capital letters to noun substantives. &c., in one place, and the omission of them in another. Whatever may be the different opinions or practices of authors in these respects, the system of spelling. &c. must not he changed in the same work.

The reading-boy should be able to read with ease and distinctness any copy put into his hands, and he should be instructed not to read too fast, but to pay as much attention to what he is engaged on as if ho were rending for his own amusement or instruction. The eye of the Header should not follow, but rather go before, the voice of the reading-boy; for, by a habit of this nature, a Reader will, as it were, anticipate every single word in his copy; and when any word or sentence happens to have been omitted in the proof, his attention will the more sensibly be arrested by it. when he hears it pronounced by his reading-boy. Great care, however, ought to be paid, least the eye of the Reader should go too far before the words of his reading-boy. For as he will be apt to be attending to the meaning of his author, he will read words in the proof which actually do not appear there, and the very accuracy of the reading-boy will but tend to confirm him in the mistake.

In revising a proof-sheet, particular care must be taken that none of the fresh errors escape, which compositors often make in the course of correcting the original ones. To avoid this, the Reader ought not only to pay attention to the particular word which been corrected, but always to read over with care the whole of the line in which that word is to be found. This is particularly necessary in cases where it has been requisite for the compositor to alter irregular or slovenly spacing; for in raising the line in the metal for that purpose, there is very great danger of some word or letter falling out, or some space being put into a wrong place.

In offices where more Readers than one are employed it is always advisable that a proof-sheet should be read over by at least two of the Readers. The eye in going over the same track is liable to be led into the same mistake or oversight. The interest excited by the first or second reading having abated, a degree of listlessness also will steal upon the mind, extremely detrimental to correctness in the proof. It ought always to be remembered that the part of the copy which contains the connecting matter of the ensuing sheet must either be retained, or carefully transcribed, or read off, a proof of that matter having been pulled for that purpose.

Authors are very apt to make alterations, and to correct and amend the style or arguments of their works when they first see them in print. This is certainly the worst time for this labour, as it is necessarily attended with an expense which, in large works, will imperceptibly swell to a large sum; when, however, this method of alteration is adopted by an author, the Reader must always be careful to read the whole sheet over once more with very great attention before it is finally put to press.

A proof-sheet having duly undergone this routine of purgation, may be supposed as free from errata as the nature of the thing will admit, and the word “Press” may be written at the top of the first page of it. This is an important word to every Reader if he have suffered his attention to be drawn aside from the nature of his proper business, and errors should be discovered when it is too late to have them corrected. This word “Press” is as the signature of the death-warrant of his reputation; and if he is desirous of attaining excellence in his profession will occasion an uneasiness of mind which will but ill qualify him for reading other proof-sheets with more care and correctness.

A Reader should, therefore, be a man of one business, always upon the alert, all eye, all attention. Possessing a becoming reliance upon his own powers, he should never be too confident of success. Imperfection clings to him on every side, errors and mistakes assail him from every quarter. His business is of a nature that may render him obnoxious to blame, but can hardly be said to bring him in any very large stock of praise. If errors escape him he is justly to be censured, for perfection is his duty. If his labours are wholly free from mistake, which is, alas, a very rare case, he has done no more than he ought, and consequently can merit only a comparative degree of commendation, in that he has had the good fortune to be more successful in his labours after perfection than some of his brethren in the same employment.

No Reader should suffer his proofs to go to press, where there have been any material errata, without their receiving a last revision by himself. If he is doubtful of himself and diffident of his own powers of attention, how much more ought he to be on his guard respecting the care and attention of others! He should make it a rule never to trust a compositor in any matter of the slightest importance—they are the most erring set of men in the universe.

In the final operation of revising a form for press, the eye must be cast along the sides and heads of the respective pages least any letter should happen to have fallen out, any crookedness have been occasioned in the locking-up of the forme, or any battered letters have been inserted. These are the qualifications of a Reader; this the business of one employed as a Corrector of the Press. It is an arduous employment, an employment of no small responsibility, and which ought never to be entrusted to the intemperate, the thoughtless, the illiterate or the inex-perienced. “Chambers’s Encyclopædia,” Vol. III., p. 255, has an article on Correction of the Press.

In printing regular volumes, one sheet is usually corrected at a time but where extensive alterations, omissions, or additions are likely to be made by writer or editor, it is more convenient to take the proofs on long slips, before division into pages.

The thankless and monotonous business of a Corrector or Reader is more difficult than the uninitiated would believe. It requires extensive and varied knowledge, an accurate acquaintance with the art of typography, and, above all, a peculiar sharpness of eye, which, without losing the sense and correction of the whole, takes in at the same time each separate word and letter.