Analysis

This analysis is based on data extracted from the compilation of the digital edition of Iconographic Encyclopædia and visually explores statistics about its plates, the figures within, and the accompanying text.

This analysis is based on data extracted from the compilation of the digital edition of Iconographic Encyclopædia and visually explores statistics about its plates, the figures within, and the accompanying text.

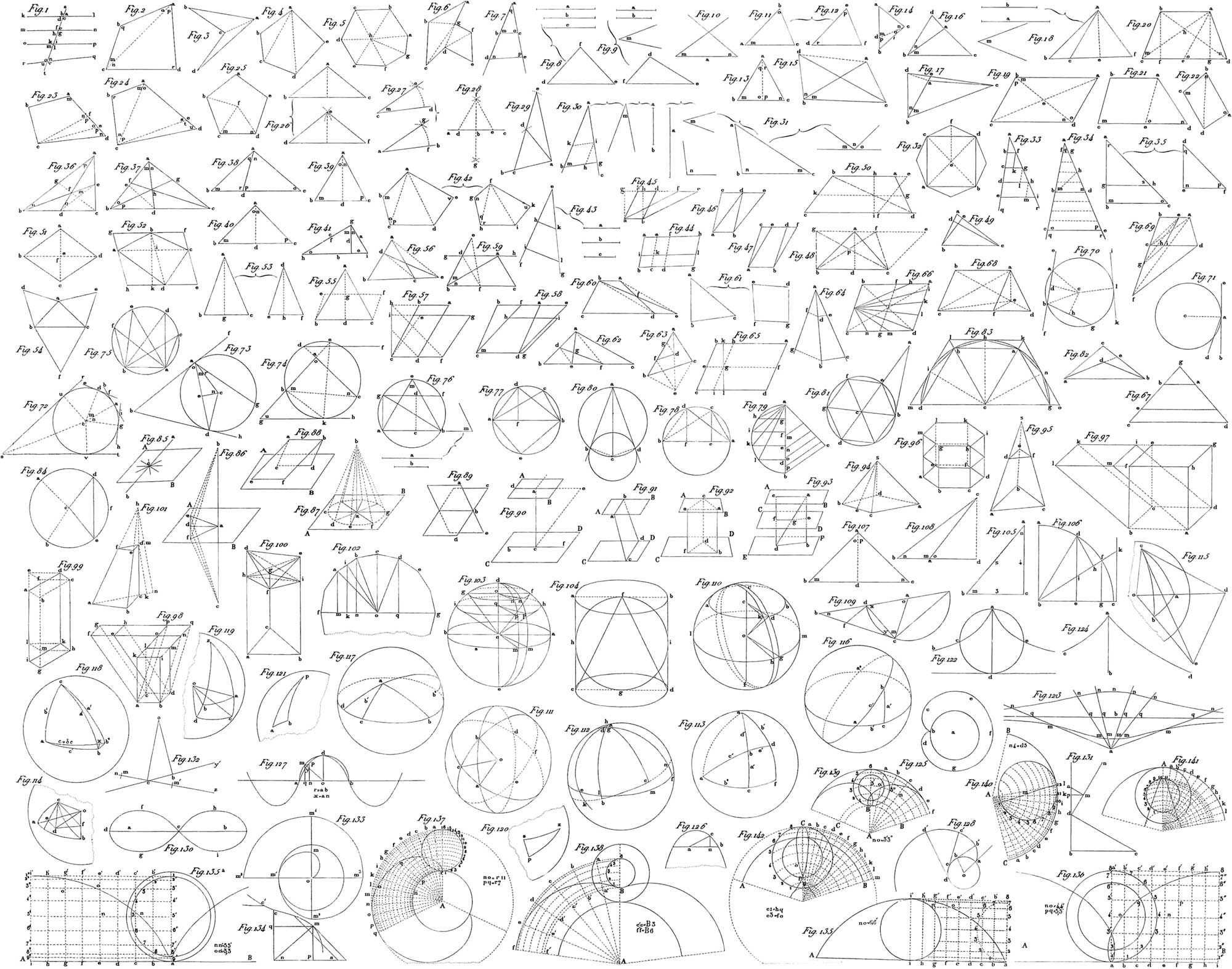

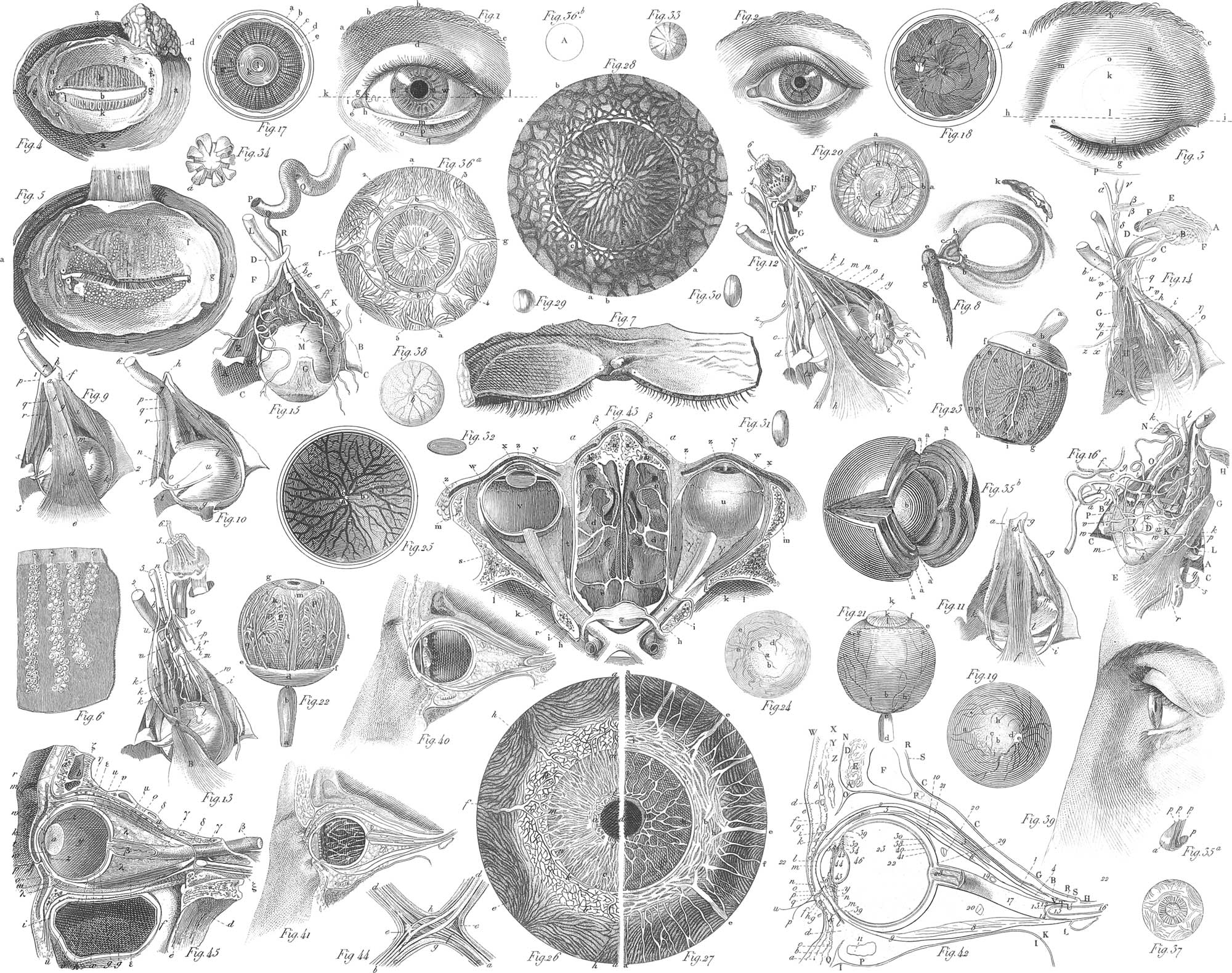

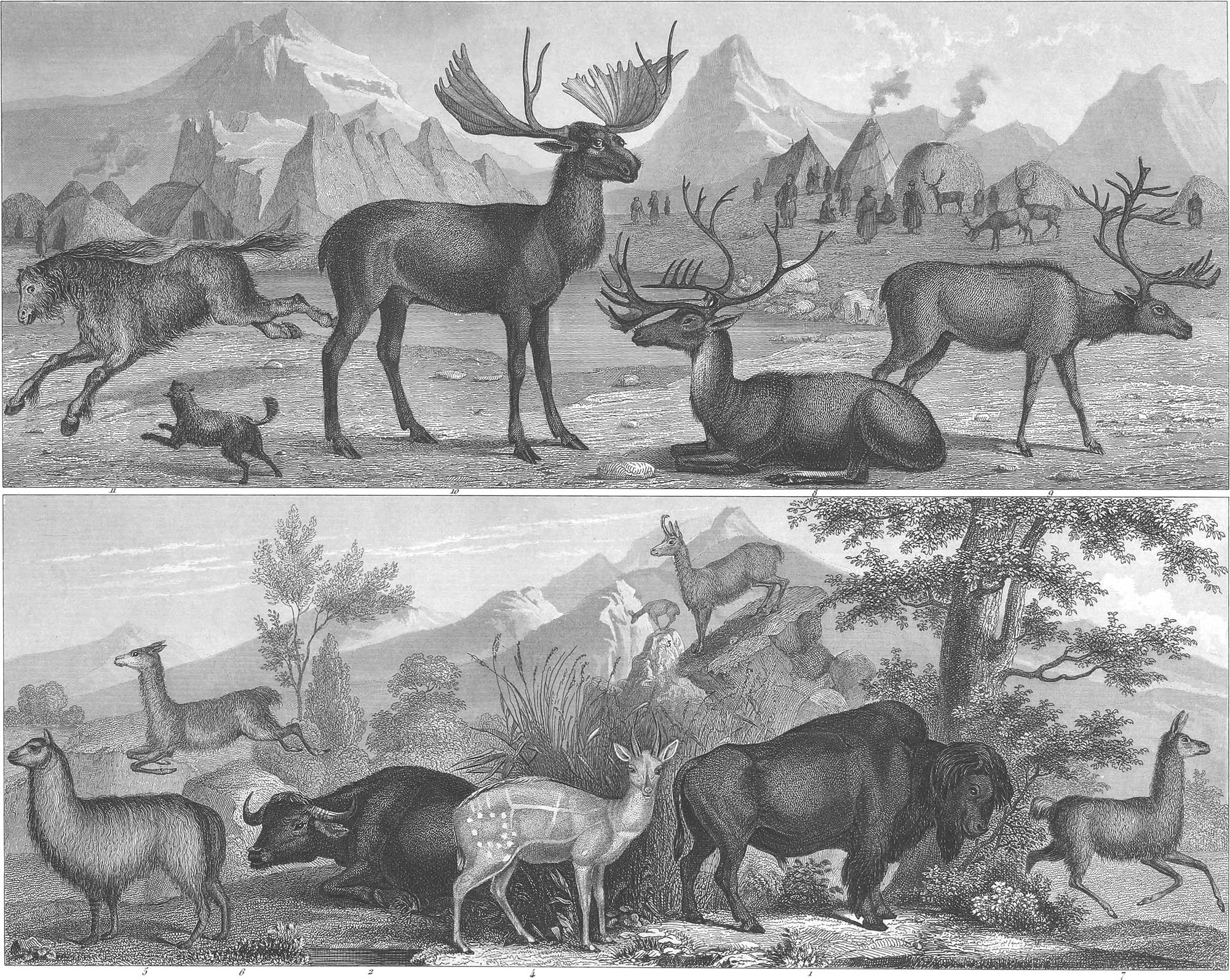

Iconographic Encyclopædia comprises 13,329 figures spread across 500 plates—each one an impressive feat in steel engraving. The plates cover a wide range of topics grouped into 18 broad subjects.

With 81 plates, History & Ethnology tops the list at the most plates while Chemistry has the fewest at only 2. Subjects in the first third of the encyclopedia like Mathematics and Astronomy contain fewer plates but many more figures on each plate illustrating simpler topics like geometry or types of telescopes. Later subjects like Zoology or History & Ethnology contain more plates but fewer figures on each illustrating more elaborate topics and full scenes like species of birds or medieval life.

Illustrations were drawn in three distinct formats:

The densest plate with 210 figures was plate 81 in Zoology, which contained figures about various insects and water-dwelling animals. With so many figures, it could have easily been split into two separate plates but was kept as one. Botany and Physics had some of the densest plates at more than 70 figures per plate while most of the plates in Geography & Planography have only 1 figure—though it depicts a very detailed map. The latter was also the only subject to have extra large plates that were essentially two plates meant to be viewed together: Plates 2 & 3 showing a map of the mountain and river systems of Europe and plates 15 & 16 of the Europe’s railroads.

Each steel plate was meticulously engraved by a one or two of 28 total engravers, whose names appeared at the bottom right of the scan of each plate. These names are not visible in the images of the digital edition but are included in each plate’s caption. Henry Winkles engraved the vast majority of plates at 345—engraving at least one plate for all subjects. Only one plate—Geography & Planography, plate 11—is missing a credit to its engraver, who is likely also J.L. v. Baehr. 31 plates also had multiple engravers—the most common pairing being R. Schmidt and Mädel III. One engraver’s name is spelled three different ways on the seven plates they engraved: “W. Hohneck / W. Honeck / W. Honek.”

More than 1.6 million words of descriptions accompany the many of figures showcased in the encyclopedia and are an impressive feat in their own right. They range from just a few words to describe any given figure to lengthy descriptions that cover a topic in great detail.

One line (—) = 1,000 words

Sprinkled throughout these descriptions are references the figures on the accompanying plates. References include just one figure (e.g., “fig. 5”) or several figures (e.g., “pl. 3, fig. 45–47”). The original intent was for readers to use these references to find the appropriate plate and see the figure being described—a tedious and sometimes challenging task considering many references don’t include a plate number, requiring readers to keep track of which plates were being described.

Most of the 13,329 figures were mentioned at least once in the entire set of descriptions but 774 (6%) are never mentioned. Six plates were mentioned but their individual figures were not referenced even though they were described in the table of contents. Many figures were referenced several times depending on what aspect of them was described. Anthropology & Surgery had the most repeat references because several plates contained diagrams of the entire human form and the description covered many aspects of it such as bones, the vascular system, and muscles. The figure with the most references was figure 3 on plate 122 in Anthropology & Surgery, which was referenced 25 times.

One dot (•) = 1 figure per 5,000 words

Zoology was the longest with around 262,000 words but had an average density of figure references. Mineralogy was the shortest with approximately 22,000 words and the densest with the most references at around 95 figures for every 5,000 words. In contrast, Geography & Planography is the least dense with around 83,000 words (an average length) and 5 figures for every 5,000 words.

Laying the subjects out end-to-end and marking where every figure occurs creates the following timeline which shows where figures are referenced with circles and is color-coded by subject. Larger circles means more figures referenced at once. Most references only include one figure but many include 3 or 5, with the most including 65. The length of each subject is proportionate to the length of the text (subjects with more text appear as longer sections).

Four editions this encyclopedia have been published to date—each one building upon the last.

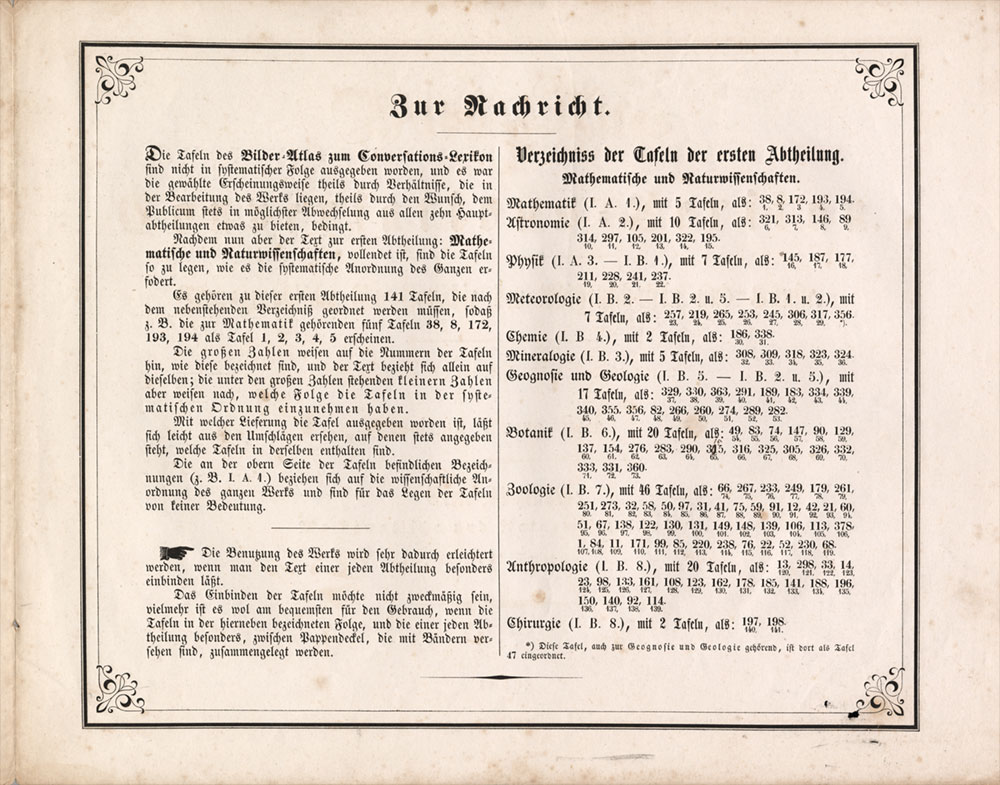

The original German edition, titled Bilder-Atlas zum Conversations-Lexicon. Ikonographische Encyklopädie der Wissenschaften und Künste, was compiled by Johann Georg Heck and was released as a supplement to Brockhaus Enzyklopædie, a German encyclopedia.

This edition was released in 10 divisions: natural sciences, geography, history and ethnology, ethnology of the present, warfare, shipbuilding and marine life, architecture, mythology or religion, fine arts, business sciences (technology). High-resolution scans of the original German illustrations are available from the David Rumsey Map Collection and scans of the entire first division of the descriptions are available from the Biodiversity Heritage Library.

Heck’s work was later translated to English and released as Iconographic Encyclopædia of Science, Literature, and Art by the Spencer Fullerton Baird, who would later become the first curator of the Smithsonian Institution. It was released in six volumes: a two-volume set of plates and a four-volume set of the descriptions. Scans of the entire English edition are available on the Internet Archive as uploaded by the Smithsonian Institution: (Plates, vols. 1, 2); (descriptions vols. 1, 2, 3, 4)

Portions of the descriptions were also rewritten for the translation, including the entire second volume covering botany, zoology, anthropology, and surgery. As stated in the English preface:

Written in and for Germany, the different subjects were treated of much more fully in relation to that country than to the rest of the world. In some articles, too, owing to the lapse of time or other causes, certain omissions of data occurred, which did not allow of their being considered as representing the present state of science, or as suiting the wants of the United States. This, therefore, has rendered it necessary to make copious additions, alterations, and abridgments in the respective translations; while, in some instances, it has been thought proper to re-write entire articles.

With these changes also came adjustments to the subjects covered and how they were organized. The list below highlights the changes between the German and English editions.

In addition to changes in descriptions, several plates were modified or entirely redesigned. The first notable change was with the first two plates combined into one and a new centerpiece figure was added. The labeling of the figures is unlike any other plate. Two numbers were given to each figure from the original second plate—the first being a continuation of the numbering from the figures on the first plate and the second, the original number from the second plate in parentheses. For example, the numbering includes: …54, 55, 56 (1), 57 (2), …

The most significant change occurred on 7 plates in botany: plates 55, 56, and 57 included the same plants but drawn differently; plates 58 and 59 were combined into a single plate; and 60 and 61 were also combined. These changes were likely related to the rewrite of the second volume of descriptions.

A minor change was made to plate 30 in military sciences to include cockades from various 36 locations along with a color legend. The center line was also removed. None of the cockades were mentioned in the description.

A remastered version of the English edition was later released in 1979 under the title The Complete Encyclopedia of Illustration. This edition included plates from the English edition reproduced with fine-line offset lithography as described its introduction, which also includes summaries of the illustrations found in each subject. Paul Bacon wrote the foreword. Two key differences of this edition compared to its predecessor are the absence of the descriptions but the addition of new titles for all of the plates.

Only one plate’s design was changed in the remastered edition. Both the German and English editions included six hilt designs at the bottom next to the three legends but they were left off the remastered edition.

Based on scans of the English edition from 1851–1852 and incorporating plate titles from the remastered edition, this website was created to restore and integrate illustrations with descriptions into a single comprehensive edition. Scans of illustrations were restored and made available free for download under a public domain license. New additions included analysis and artwork based on data derived from previous editions. Plates and their figures were incorporated with their descriptions facilitate easy reference, resulting in an interactive experience that the author hoped would honor the original intent from more than 170 years prior.